We arrived in Boulder, Colorado, on September 1, two days before Kilian Jornet was scheduled to start his latest mega endurance project, States of Elevation. If you have been living under a rock for the last month and haven’t seen the viral posts or steady stream of editorial stories, let us quickly explain.

Jornet set a goal to climb every peak over 14,000 feet (“fourteener”) in the contiguous U.S. in just a month, all under human power. He started in Colorado’s Front Range, running up 14,259-foot Longs Peak and completing the LA Freeway in his first day—a mega endurance feat in itself. But he was just getting started.

That night he biked 49 miles, got a few hours of sleep, and spent the next 15 days summiting the other 55 fourteeners in the state. He then pedaled 900 miles across the desert to California, completed all 13 fourteeners in the Sierra in just 56 hours (18 hours faster than the previous fastest known time), biked north to Shasta, climbed it, and biked further north to Mount Rainier, finishing the entire project, roughly 3,200 miles and 400,000 feet of elevation gain, in just 31 days.

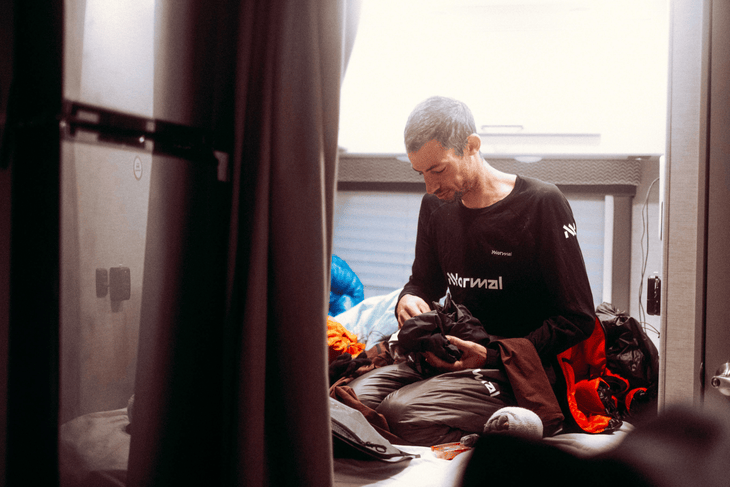

OK, back to a driveway in Boulder suburbia. While Jornet was packing his cycling, climbing, and running gear in the RV that would be his home-away-from-home for the next month—if you can call 3-4 hours of sleep each night home at all—we were refining the details of our creative plan for the first week, making contingencies to said plan, and contingencies to those contingencies. With a project this big, you truly have to be ready for anything.

4 Lessons from Trying to Keep Up with Kilian Jornet

The two of us have been fortunate to document a lot of athletes over our careers—from Olympians to pros on remote expeditions—but following Jornet is different. Even after weeks of non-stop movement, he’s liable to drop you on any given climb. Making it more complicated is that Jornet is so capable on technical terrain that keeping up on the scrambling sections, of which there were many, bordered on impossible. Very few humans can move like Jornet in the mountains, which made our task, errdifficult.

Two days after Kilian wrapped the project, as we aired out our camping gear and edited our last batch of photos, we sat down to discuss what we learned from this project, from one of the greatest endurance athletes of all time.

1. Replace Perfectionism With Spontaneity

Nick Danielson: Ten days into the project, I found myself waiting for Kilian on top of Challenger Point, a fourteener in the remote Sangre De Cristo range of Colorado. I had climbed 6,000 feet of elevation just to get there, while soaked by a cold September storm. The payoff was an unobstructed view of the range’s formidable link up of fourteeners, the Crestone Traverse, with a fresh dusting of snow. Right above me was a perfect window where I envisioned lining up Kilian with a small light spot of rock of Crestone Peak behind him.

Kilian appears and I see him looking for the standard descent, but instead he chooses the direct line down a steep system of ledges that will bypass my plan. Disappointed, I fire off a few shots, then start to move. The tedious terrain slows him down and presents me with the opportunity of time. So, I switch to video and shoot a long slow zoom, a shot that would become a favorite of mine from the entire trip. If all had gone to plan, I would be writing that a perfect shot takes a blend of creative vision and intentional setup, but that’s not what happened and truthfully, that’s not very representative of this project.

Moments like this showed me that these projects are not about bringing the camera with the most megapixels, positioning in the perfect location, and nailing the hero shot that was on the moodboard. Attempting that will only result in heartbreak and missed opportunities. When you are on a 30-day project with a vague timeline and dozens of unpredictable factors, you need to lean into the imperfection to create imagery that you can’t predict. Let the ambiguity inspire and motivate you.

If all had gone to plan, I would be writing that a perfect shot takes a blend of creative vision and intentional setup, but that’s not what happened and truthfully, that’s not very representative of this project.

Andy Cochrane: Couldn’t agree more. I had a similar moment a few days earlier, when I hiked up the backside of Mount Massive, hoping to meet Kilian near the summit. Without service to check his tracker, I was worried I would be too late, so I redlined to the top. Sweaty and disheveled, I made it to the summit as golden hour lit up the ridge to the west, but Kilian was nowhere to be seen. I waited as the soft light turned to blue hour, then I decided to continue on, eventually rendezvousing with Kilian near dark. Instead of calling it a day, I switched to a prime lens and bumped the ISO, giving the images more grain and mood. As it would turn out, they are some of my favorites from the entire trip.

Leaning into spontaneity quickly became the name of the game. Most photo work—portraits, fashion, fine art, street, or even sports photography— is defined by rules like leading lines, negative space, and the rule of thirds, but on this project we threw out the rulebook, capturing the moment as raw and immersive as possible, without worrying about technically perfect shots. If you want to bring viewers along for the ride, use the tools at your disposal and the light you’re given, even if those photos would fail an art class.

2. Know When To Run—And To Rest.

Andy: On the third day, I met up Kilian on Argentine Pass in central Colorado, a few minutes after a pair of loud thunderclaps and hail began to fall. We chatted about our options and decided to get off the ridge, not wanting to risk getting stuck up high in a lightning storm. By the time we reached the valley floor, the storm had passed, so we rallied up 14ers Grays and Torryes at sunset. We eventually returned to the cars around 11 p.m. It was like three or four vastly different days in one.

On the long descent in the dark, I found myself contemplating balance. Spending nine-plus hours with Kilian was incredible, but certainly not sustainable. Some days I would need to bring snacks, layers, and a headlamp to go into the night. Other days I would need to play the long game, shoot selectively, and find a coffee shop to dive into the edit cave. Knowing when and how to make that call became crucial.

It goes without saying that we ran a lot, despite only a fraction of what Kilian did. Most of our access points were spur trails, often six or more miles one way, which meant the distance added up quickly. My largest day was 38 miles with 9,000 feet of vert, all with camera in hand. Over his two weeks in Colorado, Nick covered 225 miles with just under 80,000 feet of climbing. But good fitness was just table stakes for the project—even more important was managing our energy, or risk burn out.

Good fitness was just table stakes for the project—even more important was managing our energy, or risk burn out.

Nick: Definitely. The challenge with shooting these endurance projects is that you can have a great plan but so much is out of your control. For example, when we got to the Nolan’s 14 route in the Sawatch Range, we were met with thunderstorms that pushed Kilian’s timeline back by hours. The night was starting to descend when he got to me, as was another bout of rain. He took some time at my truck to eat a nutella sandwich and warm up before embarking on the linkup of six fourteeners. I sent him off to push through the next 14 hours alone and in the rain.

It’s a weird feeling to be sitting at a burrito joint in Buena Vista, editing photos and hiding from the storm while your subject is out there. It’s also weird knowing that you are going to be missing imagery from a large portion of one of the more recognizable parts of the entire project. It’s easy to feel guilty for not making a greater effort, in the face of someone making such a massive one of their own.

In these moments I remind myself that the point of the project is not the documentation. Kilian is not here so that I can take a photo of him and just because we did not document a piece of the story does not invalidate his efforts. We are brought on these projects to give a glimpse into the world and this requires a balance. There were numerous times I could’ve gone out for more miles, but knowing where to spend your efforts during a month-long project becomes critical, fast.

3. Be As Present As Your Subject

Nick: Last year, near the end of the Alpine Connections project, I was waiting for Kilian at the foot of a glacier in the Mont Blanc area. He arrived and I routinely, uncreatively, inquired “how are you?”

He responded, “I’m here.” There was an intensity and quiet truthfulness to this. “How was your day?” he followed. Much more was implied behind his concise greeting, but in its simplest form I think he was just wildly and fully engaged. A constant level of commitment to the place he was in, at that exact moment in time, for nearly three weeks. Few people can dream up projects like Alpine Connections or States of Elevation, but the all-encompassing presentness is more accessible for the rest of us than it appears.

Few people can dream up projects like Alpine Connections or States of Elevation, but the all-encompassing presentness is more accessible for the rest of us than it appears.

Being on these projects with Kilian is a gift—they are both fully immersive and highly demanding, and it’s a privilege to be able to dedicate three, four, or five weeks to your craft. You owe it to your subject to be fully present and in turn, you will create better work if you do.

Andy: And once you see this type of work as a gift, it doesn’t feel as hard or long or stressful, which allows you to be more creative in how you shoot. I started to see every day as an opportunity to create new types of images and grow my skills, which obviously brings out the best in anyone.

On our second day in the Sierra, I set my alarm for 3 a.m., just to check on Kilian’s progress through the night. I was surprised to see he was nearly ten hours ahead of schedule, forcing me to crawl out of my sleeping bag, hop in the driver’s seat, and rush to the trailhead. I ran up Kearsarge Pass, to (hopefully) meet him around sunrise. Typically this isn’t my ideal morning by any stretch of the imagination, but in the moment I was just grateful to have opportunities that push me to expand my craft.

Ironically, Kilian decided to take a nap around 4 a.m., right after I lost service. That meant I didn’t see him for sunrise, but instead got to watch sunrise above Sequoia National Park— and how often do you get to say that? We linked up a couple hours later and ran ten miles together, crossing the iconic Rae Lakes area. Over that stretch, I lost count of how many times he said “it’s beautiful.” Kilian is in awe of the natural things around him, from old trees to striations in the rock, encouraging me to do the same in my photos. Little things like pole grips or sly smiles became the defining pixels in those images.

4. It’s A Team Sport

Andy: Some days following Kilian was easy, but most days we had to work for it. On the first morning of the project I hiked up Longs Peak an hour ahead of Kilian and his first pacer of the project, Kyle Richardson, climbing an icy fifth class route called the Cables to get a shot at sunrise. The two chatted casually while moving so fast up the technical scramble to the summit, I was full on redlining to keep up. Right after I texted the crew group chat, “Am I getting hazed?”

I was full on redlining to keep up. Right after I texted the crew group chat, “Am I getting hazed?”

Near the end of the trip, Nick dealt with 60 mph winds and snow on Mount Shasta, helping bring viewers into the moment. In between we both experienced rain, snow, and plenty of days that ended at 2 or 3 a.m., after long slogs out in the wilderness.

Although most of these moments were solo, the two of us stayed in contact via satellite texting, while one of us was in the backcountry. This allowed us to tweak the plan, share updates, coordinate moves, or just heckle each other. You can do a lot in 140 characters to support each other and keep morale high.

Shooting doesn’t have to be a solo art. In fact, it’s probably better as a team. Riffing on ideas, styles, and gear helped me grow, not to mention motivate me during the long, wet, and grueling days. It’s always better when you know someone has your back.

Nick: Truly incredible the emotion you can convey in a concisely worded InReach message. When attempting to find creative support for the remote parts of this project, there were a lot of qualities I was looking for in a photographer. But perhaps above all else, I stressed finding someone who was capable of being self-sufficient in mountain terrain. Someone who could be autonomous and I could trust would deliver good content without hand-holding.

I found this in Andy, however, one of the things I wound up cherishing the most was not that I didn’t have to worry about Andy when he was out on the trail at 3 a.m. having “a stare down with some large animal in the bushes” (an actual inreach message I received) but instead were the miles that we found ourselves running and shooting together.

These moments didn’t make the most sense logistically—one of us should probably have been resting or eating or editing—but feeling like you’re creating something together and sharing in that memorable experience was a nice reprieve from all the moments that I spent alone over these 31 days. There are times to be strategic in the execution of these projects, but there is also always room for enjoyment. Part of why we are attracted to this work is because it is challenging, yes, but what keeps us doing the work is the love we have for it. Make sure you always find space for those moments.

The post Chasing Kilian Jornet is Just About Impossible. Ask These Two Photographers. appeared first on RUN | Powered by Outside.

🏨 Race Weekend Accommodations

Getting good sleep before your ultra is crucial. Find comfortable, affordable accommodations near your race start.

Leave a Reply